November Editorial

Bonham's meteorite auction

November Editorial

Bonham's meteorite auction

|

|

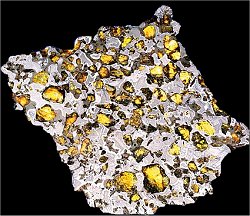

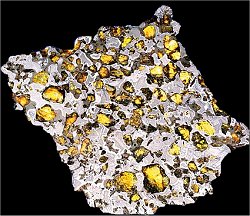

Auctions of world-famous meteorites don't happen every day, so it is not surprising that the auction of 53 specimens at Bonham's New York gallery received a lot of attention. The sale took place on the 28th of October 2007. Most of the meteorites up for grabs came from the coveted Macovich Collection, which is owned by a small number of enthusiasts with Darryl Pitt as curator. All the Collection's specimens are up to the museum standard and they come from some 500 meteorite falls. Over the years the Macovich Collection has supplied specimens to numerous private and institutional collectors, including the Smithsonian, London's Natural History Museum, the Academy of Sciences (both in Beijing and Moscow) and the American Museum of Natural History, New York. The Bohham's auction, apart from the most expensive items, most of the specimens on offer were sold. The heaviest item that passed under the auctioneer's hammer was a meteorite fragment from the famous Sikhote-Alin meteorite which fell in February 1947 approximately 440 km northeast of Vladivostok in Russia. This specimen weighs 99.5 kg and is claimed to be the largest fragment of this famous meteorite to be found outside Russia. Shikhote-Alin is composed of 93% or iron and 5.9% nickel. What makes this specimen even more valuable is its shape, as there is a distinctive a fissure running along its entire length. The most valuable specimen offered for auction was a piece of the Willamette Meteorite, valued at somewhere over a million dollars. The Willamette, discovered at ground level in the Oregon woods, is famous for being the largest meteorite recovered in North America. It is believed that the meteorite fell in Canada and was deposited in Oregon by glaciers or floods during the last Ice Age. More controversial than the origins of the meteorite is the question of its ownership. The Willamette meteorite was 'discovered' in 1902 when a miner named Ellis Hughes noticed it on property belonging to the Oregon Iron & Steel company, which lay adjacent to his own claim. Immediately recognizing the potential value of his discovery, the miner set about exploiting it. With only a horse and cables he managed to move the 15.5 ton mass of nickel-iron from its original location to within the boundaries of his property; although it apparently took him quite a few months to do so. With the meteorite safely on his land, the miner started charging a fee for tourists to view it. Business went well, and such was the growing fame of the meteorite that that the press covered the story. Among those who came to view the meteorite was an attorney from Oregon Iron & Steel. He noticed the drag marks leading back to his employer’s land, and this led Oregon Iron & Steel to sue and win possession of the meteorite. The company subsequently sold it to Mrs William E Dodge who offered it to the American Museum of Natural History. The meteorite has now been on display in this museum for almost a century and has been viewed by some 50 million people, but its turbulent history has not ended. In 1990, tens of thousands of Oregon school children signed petitions to have the meteorite returned to their state. A bill was proposed in support of the idea in the U.S. Senate and an Oregon congressman advanced the notion of withholding federal funding earmarked for the museum until the meteorite was returned. A concerted effort was made to convince the childrens’ mentors to discontinue their effort - and the childrens’ campaign was eventually dropped. In 1999, a coalition of tribes of Oregonian Native Americans, The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, filed a claim to have the meteorite returned to Oregon by invoking the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA)—typically used to retrieve burial remains and crafted artifacts. In response to the Grand Ronde’s invocation of NAGPRA, the museum filed a lawsuit in federal court in which the Grand Ronde’s claims were contested. The parties eventually settled out-of-court and requested a declaratory judgment that the meteorite was museum property. The Willamette meteorite remains the centerpiece of the Rose Center where there is now a sign indicating the meteorite’s spiritual connection to the Grand Ronde’s predecessors. There is also an agreement that the meteorite can never again have fragments cut from it. One of my favorite pieces at the auction in Bonham's gallery was a slice from Glorieta Mountain meteorite. This meteorite is a pallasite - a stony-iron meteorite which contains crystals of olivine suspended in the nickel-iron matrix. Only 1% of all meteorites ever recovered have been pallasites and the Glorietta is the most coveted. What makes it exceptional is that the meteorite is chemically and morphologically unique - so much so that researchers have been forced to reclassify it as its own subtype. Apart from olivine crystals this meteorite also contains peridot crystals which are surrounded by bands of kamacite and taenite — the two alloys of nickel-iron that comprise most iron meteorites. The beautiful piece offered for sale was among the larger slices taken from the main body of the meteorite and was another specimen which had previously belonged to the Macovich Collection.

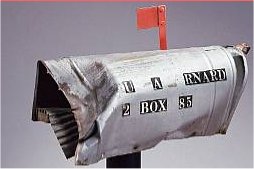

Another famous specimen up for sale was a fragment of the Valera Meteorite. This is famous, not for its composition, but as the only meteorite which is documented as having killed a mammal - the actual victim being a cow. On the evening of October 15, 1972 farmhands in Trujillo, Venezuela were startled by an inexplicable sonic boom. The next morning a large, unusual rock was found alongside the carcass of a cow with a pulverized neck and shoulder. In addition to famous meteorite fragments, there was a mail box offered for auction. While hundreds of buildings and nearly two dozen cars have been struck by meteorites, there is only one mailbox known to have received an extraterrestrial special delivery. It happened on December 10 1984, in Claxton, to a mailbox belonging to a Ms Carutha Barnard. The forceful impact of the meteorite blew off the mailbox's rear plate. Soon afterward the unfortunate mail box was bought up by meteorite collector and tektite expert Hal Povenmire. He sold it on to meteorite dealer Blaine Reed who sold it to - you guessed it - the Macovich Collection. The Claxton mail box was auctioned off for a mere $70,000. To see the full list of meteorites auctioned in Bonham's New York gallery go to: www.bonhams.com and look for sale results on the 28th of October. |

| _______________________________ | ||||

| Home | | | Shopping | | | Database |

© Biscuit Software 2004-2015

All rights reserved