January Editorial

The mystery of Burgess Shale

January Editorial

The mystery of Burgess Shale

|

|

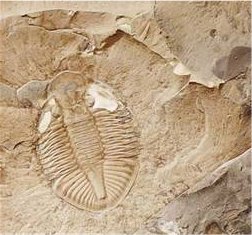

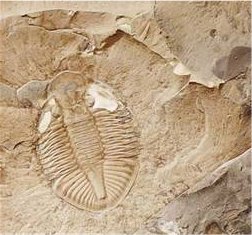

The Burgess Shales are fascinating - not least because they are 500 million years old, but also because unlike most fossils the soft tissue of animals in the the Burgess Shale has also been fossilized, preserving minute details. But there is a huge paradox which has been fascinating scientists ever since the discovery of the Shale. These fossils were originally buried deep in the Earth’s crust and heated to over 300°C (~600 °F), before being thrust up by tectonic forces to form a mountainous ridge in the Rockies. Usually such extreme conditions should have destroyed the fossils and at least destroy all remnants of fossilized soft tissue. The Burgess Shales are a hidden treasure situated within the Yoho National Park in the Canadian Rockies. The fossils were discovered in 1909 by Charles Walcott, palaeontologist and Secretary to the Smithsonian Institution, who quickly recognized the unique nature of the specimens. For the next fifteen years he would return to the site almost every year establishing a quarry on the flanks of Fossil ridge. He uncovered and described thousands of specimens some of which are now on display in the Smithsonian Museum (http://paleobiology.si.edu/burgess/burgessSpecimens.html). However in the 1920s the Burgess Shale fossile were generally regarded as little more than curiosities. It was not until the 1960s that a first-hand reinvestigation of the fossils was launched by Alberto Simonetta and their real significance became apparent. The fossiliferous deposits of the Burgess Shale are a collection of sightly calcareous dark mudstones dating to about 505 million years ago. It is believed that Burgess Shale animals lived in a warm shallow sea. Periodic mudslides would transport the animals in the mud to the base of the reef where they were buried and died. Over the course of many millions of years, the animal remains were under layers of sediment and their bodies turned into fossils. The fossils were at one time covered by up to 10 kilometres of overlying rock, and would have been subjected to great heat and pressure at those depths. About 175 million years ago, mountain-building forces bulldozed and transported the fossils from their ocean burial-ground many kilometres eastward to their current position high on a mountain ridge in Yoho National Park. Taking the extreme conditions the fossils were under during these millions of years it is hard to believe that these fossils not only survived but survived preserving fossilized soft tissue and all. But now scientists in the United kingdom from the University of Leicester and from Cambridge University think they can explain the prefect preservation of these fossils. In a paper published in the November issue of Geology (Page, A. et al., Geology, 2008, 36, pp 855-59) they report on detailed studies of the Burgess shale fossils carried out by Alex Page and his colleagues. The scientists showed that as the delicate organic tissues of these sea animals were heated deep within the Earth, they became the site for mineral formation. The new minerals, forged at these tremendous depths, picked out intricate details such as gills, guts and even eyes. As Alex Page points out: “This provides a whole new theory for how fossils form. The deep heating may not have cremated them, but it certainly left them stone baked.” It is yet to be seen whether the new study will put to rest a century-old debate. |

| _______________________________ | ||||

| Home | | | Shopping | | | Database |

© Biscuit Software 2004-2015

All rights reserved